2023

June 25

Victoria Contra El Cortito Logo.

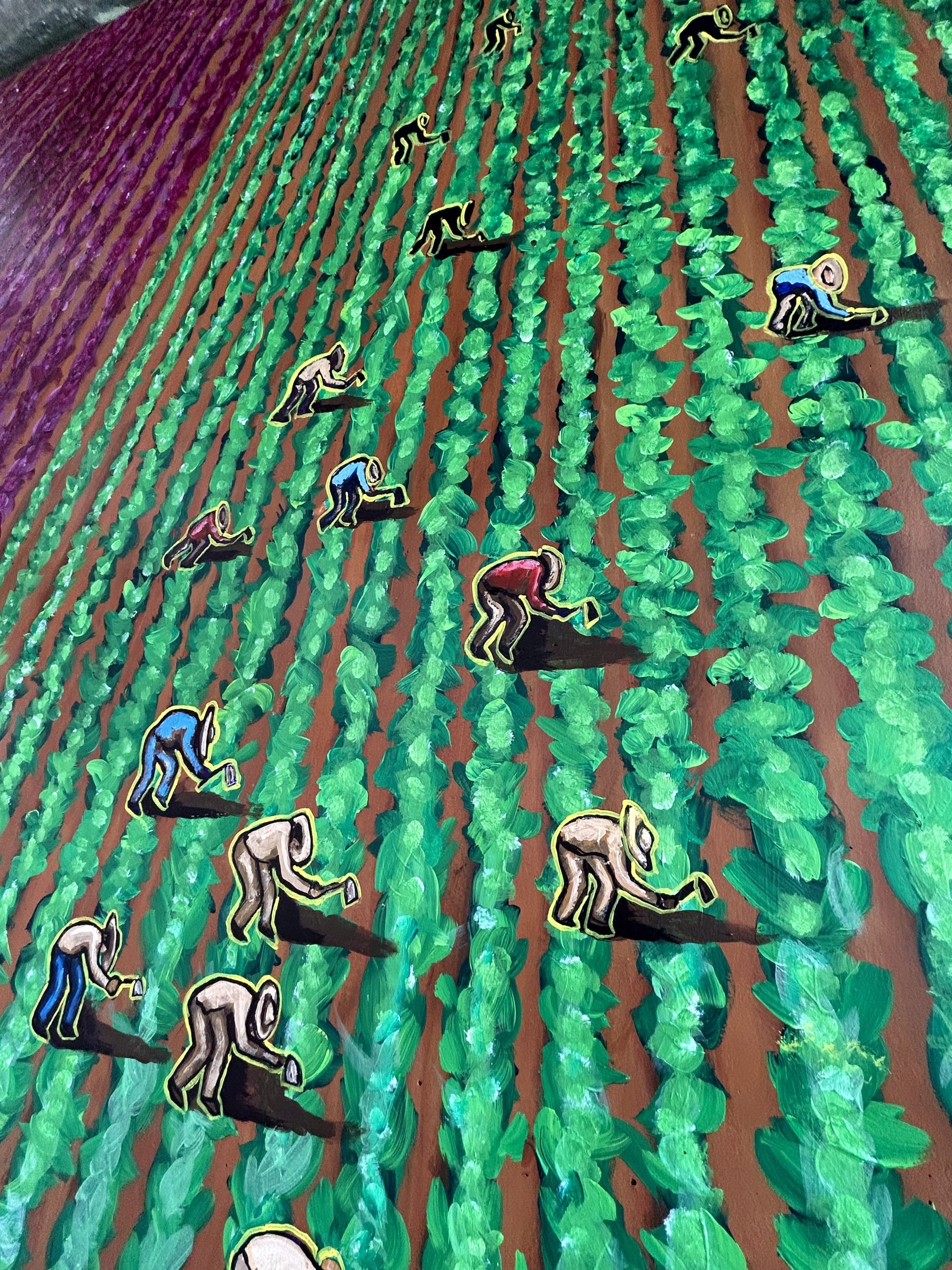

“Victoria Contra El Cortito” Mural

On June 25, 2023, the Friends of El Cortito Mural Project and the Chicano Park Steering Committee unveiled the “Victoria Contra El Cortito” mural. This mural is a tribute to a landmark case that in April of 1975 banned the use of the short-handle hoe, called “el cortito” by farm workers. Use of the unsafe hand tool caused irreparable injury to thousands of farm workers backs throughout California and other parts of the nation. The mural honors the work and sacrifice of these farm workers. It is a reminder to all people that with the “Si Se Puede” spirit of hope and perseverance, injustice and harm may be eliminated.

The Past

BrutalityFW-scaled

The Past

It is believed that at the end of 19th century in the California fields, the short-handle hoe was introduced. The eight-inch hand tool was forced upon farm workers by the growers to use for weeding and thinning lettuce, bell peppers, squash, strawberries, sugar beets and other crops. During the 1940’s, the Mexican braceros were forced to use the short-handle hoe and called it “el cortito.” Using the cortito, farm workers stooped over for miles thinning and weeding. Farm worker labor contractors liked the use of “el cortito” to make sure that the laborers were working and not resting. Some growers believed the use of the short-handle hoe was efficient. It made the workers careful and kept the crops from being damaged.

The farm workers despised “el cortito” because it forced them to stoop over when working. They called it “El Brazo del Diablo,” the devil’s arm.

Smithsonian (2001) Short Handled-Hoe The Object of History | Behind the Scenes with the Curators of the National Museum of American History

The Consequences

Back injuries sustained by farm workers.

The Consequences

In the 70’s in an Imperial County medical clinic servicing farm workers, Doctor David Flannigan found and explained in his testimonies during the case, that our back is a stack of bones called the vertebrae, separated by soft discs of jelled like sacks in between. When you bend over all day the discs degenerate, and in time explode. The constant use of the short-handle hoe, not only injures a young farm worker’s back, but causes them to have the spine of a seventy-year-old. There is no medical cure for the wearing and degeneration of the back, the ligaments become ragged and irregular. The disc becomes more brittle, with cracks and hardening and seepage of liquid centers, which then bulge and apply pressure on the nearby nerves and to the lower extremities. The bone fractures do not heal. The malpositioning of the body causes stress to the low back structures and leads to continuous back injury.

There was no doubt that Dr. Flannigan’s clinical practice and research on the short handle hoe plays a significant role in the development of the pathology of the lower back region and should be considered a major health hazard to farm workers. (Jourdane, 2004, pp. 101-104)

Smithsonian (2001) Short Handled-Hoe The Object of History | Behind the Scenes with the Curators of the National Museum of American History

The Struggle

Struggle2

The Struggle

The legal activism of Maurice Jourdane and Marty Glick, attorneys with the California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA), and activists of the movement Hector de la Rosa, Susan Alva and Carlos Bowker assisted in the banning of use of the short-handle hoe. They were supported by the United Farm Worker leadership of Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Gilbert Padilla, Jessica Govea, Philip de La Cruz and by local San Diego activist Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez, Father Sandini, and Daniel Hernandez. There were thousands of farm workers who used “el cortito” but a few must be mentioned because of the role they played in winning the milestone court case: Sebastian Carmona, Elena Bowker Wimer, Jessus Serrano, Angie Penunuri Quintana, Inez “Nacho” Hinojosa, and Dora Portena Medina.

The banning of using the short-handle hoe took five years to tell the story through newspaper articles, surveys, testimonies about farm worker’s health conditions, doctor’s testimony, constant regulatory hearings, and court appearances. The “Si Se Puede” spirit was not lost but became more powerful in using creative solutions to the injustice to use the short-handle hoe in the fields.

On April 7, 1975, the California Supreme Court decided that the short-handle hoe was an unsafe hand tool and sent it back to the Industrial Safety Board to enforce the ban of using the short-handle hoe. It was then created into a regulation which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law. (Jourdane, 2004)

The Portraits

Portaits in El Cortito Mural.

The Portraits

There were thousands of farm workers who were injured by this dangerous tool and the mural is in honor of them and the legal case. Thank you to the activist and other lawyers who believed that this tool must be forever removed from the fields.

The following is a list of names with their location in the mural of actual participants to either using the short-handle hoe or assisting in banning of El Cortito.

Mural facing from the left, above the Si Se Puede banner, first row Lead CRLA Attorneys Maurice “Mo” Jourdane, Attorney Marty Glick, Cesar’s musician Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez, Cesar E. Chavez and next to him Dolores Huerta founders of the UFW, Susan Alva- community investigator on case. Second row from the right, Board Member of UFW Gilbert Padilla, next to him community investigators Carlos Bowker and Hector de la Rosa, next to them Jessica Govea UFW organizer and next to her Father Victor Salandini- Tortilla Priest. Next to Priest, female farmworker with red bandana Angie Penunuri Quintana and above her Leader of Philipino Farm workers who were joined by UFW, Philip Veracruz and, below the sign of banning the hoe is farmworker Elena Bowker Wimer with white earrings. Most of these activist were Farm Workers who used el cortito.

In the Victory panel of mural with the long handle hoe farm workers are (mural facing you) at the left, Daniel “Danny” Hernandez, San Diego Community Activist who died during creation of mural and above him with a bracero hat farmworker Inez “Nacho” Hinojosa, uncle of lead artist, Mario Chacon. The rest of the campesinos with the long-handle hoe were Mario’s vision.

The Victory

The victory of the ban of the short-handle hoe and replacement with the long handle hoe.

The Victory

After the court decision and the regulation created by the Industrial Safety Board and Governor Brown’s approval to ban the use of the short-handle hoe, the newspapers across California were reporting the victory. “Since the largest lettuce producers has found the long-handled hoe gets more done in a day with less loss of stamina, other employers would appear to have no ground to stand on in offering further resistance to the ban on el cortito.” (Jourdane, 2004, p. 131).

“Cesar Chavez responded, that is the way it works, you see. As long as the grower can produce his crops cheaply, it doesn’t matter that he is destroying the workers. But when he is forced to change, the solutions appear like a miracle.” (Jourdane, 2004, p. 131)

Today farm workers still face many challenges including inflation, housing, health care, immigration issues, and the effect of climate change. This is an exemplar case that demonstrates how a few brave lawyers, farm workers, community leaders and activists stood up to the challenge to ensure that the backs of farm workers would no longer be harmed.

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta, co-founder of the United Farm Workers, in the center of the mural struggle panel.

Dolores Huerta

Dolores has expressed “El Cortito’s” relevancy to today!

“It represented so much, it was not just the fact that they can use the long-handle hoe, it was really like going for that big fight for dignity of workers So, very symbolic victory for farm workers and CRLA. When you think of someone, (like Mo or Marty) somebody who used all of (their) intelligence and strength of their personality, patience and persistence to win this lawsuit, to get rid of the short-handle hoe, this is what the “Si Se Puede” spirit is about. Using whatever we have to help those that are in need, that is what the “Si Se Puede” spirit is. Against all odds, against all obstacles we can do it, “Si Se Puede!”

Hatton, B (2014, March 28) Tribute to Maurice Mo Jourdane Cesar Chavez Service Clubs 2014 Las Mananitas Breakfast Tribute to Maurice Mo Jourdane – YouTube

Formation of “Victoria contra El Cortito” Mural

Sketch

Mural

In December of 2021, Jonathan Julio Jourdane, son of Olivia and Maurice “Mo” Jourdane had the idea that the story behind “el cortito” court case had to be told visually. Olivia Flores Jourdane contacted activist Antonio Valladolid, who set up a meeting with his muralist friend from Chicano Park, Mario Chacon. They met with Mo, lead attorney on the historical case who told the story of “El Cortito.” Chacon began to visualize the mural he would paint. Friends of El Cortito Mural was formed, and fundraising began. Olivia spearheaded fundraising and organizing efforts. Lawyers and activists from the farm worker movement and others from the community did not hesitate to honor farm workers by donating to the project. MAAC, a local nonprofit organization graciously agreed to serve as the project’s fiscal agent. In the meantime, Mario Chacon prepared the proposal of the new mural to be painted at Chicano Park and presented it to Chicano Park Steering Committee (CPSC). However, the CPSC had a moratorium on new murals being created until they concluded an inventory of the park’s existing murals and an updated procedure for new murals was adopted. After close to a year of patiently waiting for the moratorium to be lifted and submitting the proposal, in February of 2023, the committee was granted permission to create the mural at Chicano Park. The work began March 2023 by lead artist Mario Chacon and assistant artists Ariana Arroyo and Gary Harper and was finished early June 2023. The completion of the mural took a year and half to be fully funded, have a proposal written, obtain a fiscal agent, order materials and be painted.

Further information

Legal Case- SEBASTIAN CARMONA et al., Petitioners, v. DIVISION OF INDUSTRIAL SAFETY et… Carmona v. Division of Industrial Safety, 13 Cal.3d 303, 118 Cal. Rptr. 473, 530 P.2d 161 (Cal. 1975).

Jourdane, M. (2004) The Struggle for the Health and Legal Protection of Farm Workers: El Cortito. Arte Publico Press.

Jourdane, M. (2007) Waves of Recovery. Floricanto Press.

Glick, M. & Jourdane, M. (2019). The Soledad Children. Arte Publico Press.

Hatton, B. ( 2014, March 28) Tribute to Maurice Mo Jourdane Cesar Chavez Service Clubs 2014 Las Mananitas Breakfast Tribute to Maurice Mo Jourdane – YouTube.

Smithsonian (2001) Short Handled- Hoe The Object of History | Behind the Scenes with the Curators of the National Museum of American History.

With Solidarity by Friends of El Cortito Mural Project at Chicano Park.

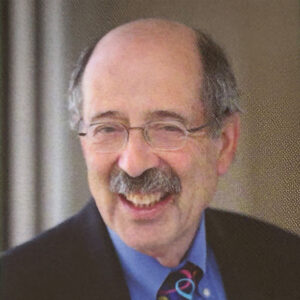

Biographies

As a young man Mo’s love was surfing. After meeting Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta in the late 60’s Mo decided to represent farm workers for over ten years, at California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA) and Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) as an attorney. Mo was determined to improve the lives of farm workers with the law. He became legal counsel for Govenor Jerry Brown in late 1970’s, a judge in Monterey County for three years in the early 80’s, and married Olivia Flores in the 80’s. He then moved to San Diego to work at the California Court of Appeal’s 4th District and raised his two children, Jackie and Jonathan. In San Diego, Mo worked as a juvenile court judge, and Assistant Attorney General for Jerry Brown, and as a lawyer for the Labor Commission under Julie Su. Mo is also an author who has published three books: “The Struggle for the Health and Legal Protection of Farm Workers: El Cortito” (Arte Publico Press, 2005); “Waves of Recovery” (Floricanto Press, 2007); “The Soledad Children- The Fight to End Discriminatory IQ Tests,” by Marty Glick and Maurice Jourdane (Arte Publico Press, 2019). Mo enjoys running and walking his dogs with Olivia.

For more information, Mo Jourdane can be reached mojourdane@gmail.com.

Olivia Flores graduated from the University of Southern California with a Bachelor of Science in Public Affairs, obtained a juris doctorate law degree from the University of San Fransico Law, received her teaching credential from the University of California, San Diego, and a Master’s in Arts in Education and Leadership from San Diego State University. Olivia went on to work as a California Health Secretary for Mario Obledo and Governor Jerry Brown in the Finance Department. She was a clerk for Justice Cruz Reynoso. Mo and Olivia met when assisting Governor Brown to appoint Justice Cruz Reynoso to the California Supreme Court. She has been married to Mo Jourdane for over 40 years, during that time she helped him recover from a near fatal car accident. Olivia took 12 years from her career to raise two children who went on to graduate from UCLA and Stanford. Jackie Flores Jourdane, received Lemon Grove Teacher of the Year and Jonathan Julio Jourdane, is a Criminal Defense Lawyer in Colorado. An educator and Principal since 1997 in the San Diego area teaching children not only how to read, write and do math in English and Spanish, Olivia challenged her students to learn the importance of their cultural history through lessons taken from the Farm Worker Movement. She retired from teaching in 2020 to assist her husband on his college speaking tour. In 2022, Olivia spearheaded fundraising and organizing for the creation of “Victoria Contra El Cortito” Mural at Chicano Park. Mo and Olivia live in San Diego helping their community.

For more information, Olivia Flores Jourdane can be reached at oliviafloresjourdane@gmail.com.

Marty Glick is currently Chief Operating Officer of the Saul Zaentz Company. He is a board member of Public Advocates in San Francisco. He retired as a litigator with the international firm, Arnold & Porter, and is listed in Best Lawyers in American in Intellectual Property and Patent Law. He worked in the Mississippi Justice Department in the 1960’s and for California Rural Legal Assistance for eight years. He has been CRLA’s outside counsel for four decades. He lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area.

For more information, Marty Glick can be reached at martyrglick@gmail.com.

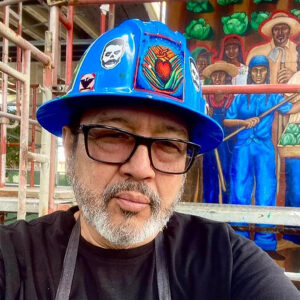

Born and raised in the Boyle Heights community of Los Angeles and coming of age at the height of the Chicano Movement in the late 60’s and 70’s, Chacon considers his experiences during the High School Walkouts, the Chicano Moratorium, and the artistic renaissance of this period to be a powerful life changing phenomena that informs his social and artistic perspective even today. Settling in San Diego, California in 1981, he has been featured in numerous gallery exhibits, and publications, and has created murals at the famed Chicano Park in San Diego and throughout the region.

Parallel to his career as an artist, Chacon served as a Counselor, and Dean of Students at the University of California, San Diego, Dean of Students at San Diego City College, and Associate Dean of Special Programs at Grossmont College. Throughout his 36 years in higher education, he served on numerous regional and statewide committees representing the needs of underserved students and held educational institutions accountable for delivery of equitable services for all students. Mario Chacon retired in 2019 to pursue his career as an artist and muralist on a full-time basis.

Chacon has also served on the board of directors, and Arts Advisory Committee of the Centro Cultural De La Raza in San Diego, The Barrio Logan Planning Group, The Kumeyaay Indian Foundation and various committees and efforts serving the Chicano community of San Diego. Most recently he has enjoyed serving on the Board of the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center and is very proud of contributing to the inauguration of this wonderful museum and repository of art, culture, history, and science.

In addition to the aforementioned, when not spending time with his children and family or at a mural site, Chacon works from his studio located at the Bread and Salt Art Complex in Barrio Logan, where he creates, and facilitates artistic development workshops with individuals and small groups.

For more information, Mario Chacon can be reached at chaconarte99@gmail.com.

Ariana Arroyo is a self-taught artist currently residing on unceded Kumeyaay territory, also known as San Diego, California. Her maternal lineage comes from Mayo Yoreme people from Sinaloa, and Buena Vista, Jalisco. Her paternal lineage comes from Ensenada, Baja California, and Apatzingan, Michoacan. She grew up on both sides of the borderlands, Ensenada, Mexico, and San Diego, California. Her reconnection to her culture came first through her reconnection with the land. Ariana has interwoven land stewardship with visionary ancestral dreams into her artwork. She is a visual artist that mainly works with acrylics, as well as watercolors, ink, charcoal, and digital illustrations.

Before she was an artist, Ariana dedicated ten years to land stewardship through working in regenerative agriculture, and land restoration with California native plants. She finds inspiration for her artwork in ecological projects regarding food and seed sovereignty, autonomous food systems of intertribal communities, traditional ecological knowledge, and the way nature and art can help bridge the gap between youth and elders affected by the urban diaspora and forced relocation of native peoples across Turtle Island. Her own personal journey navigating motherhood has led her to explore topics in her artwork involving fertility, birth work, and traditional healing practices of Mexico. She has been intentional with commissioning her artwork to organizations primarily led by black and indigenous people of color, to support the empowerment of self-told narratives on past, present, and future BIPOC issues. Ariana has illustrated numerous pieces for birth worker’s small businesses and nonprofits that are reclaiming women’s and birthing people’s reproductive autonomy from the medical-industrial complex. In 2021, she illustrated Teozinetli, a zine regarding food sovereignty and revitalization of traditional foods as medicine in collaboration with Mi Xantico. She has also created illustrations for the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative, in support of the protection and conservation of this sacred medicine and honoring its ceremonial ways for native people and future generations. She has exhibited her paintings at multiple galleries including The Centro Cultural De La Raza in San Diego, GalerÃa 1904 in Barrio Logan, and the Sagrado in Phoenix, Arizona.

For more information, Ariana Arroyo can be reached at Arroyo.ari@gmail.com.

Gary Harper is a multi-media artist and painter based in the Historic San Diego Community of Barrio Logan. He started painting at four years old and many years later, after a stint in the corporate world, decided to heed his spiritual mission and pursue the path of an artist. Since 1999, Harper has exhibited in galleries throughout California including Palm Desert, Laguna Niguel, La Jolla, and locally in his gallery studio located in Barrio Logan. Harper’s paintings are in private collections throughout the U.S. and internationally. In his own words he states, “I have to paint – art selected me, not the opposite. I have no choice in the matter.” In addition to his artistic endeavors, Harper is an interior design builder, and sign painter, and has many projects to his credit throughout the San Diego area.

For more information, Gary Harper can be reached at azulfineart@yahoo.com